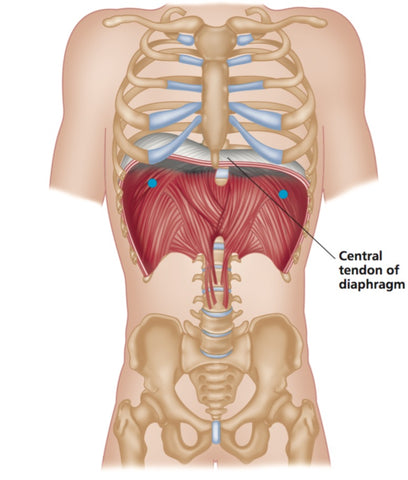

Diaphragm and Breathing

Which muscles are used for breathing?

Breathing is a complex process that involves the coordinated activity of two or three muscle groups. The muscles that play a role in breathing are diaphragm, rib cage muscles, and accessory muscles.

Diaphragm is a thin dome-shaped muscle that separates the abdominal cavity from the chest cavity. When the diaphragm contracts, the lungs are inflated and thoracic cavity expands. It also increases the intra-abdominal pressure, which draws venous blood to the heart.

Lungs are soft structures located either side of the heart. They are wrapped in a pleural membrane. There are two lobes in the left lung and three in the right. Each lobe has an upper and lower end. In addition to the lobes, the lungs are enclosed by a thoracic cage that helps enclose pulmonary ventilation. This cage is lined by cilia and mucus secreting cells.

When you breathe in, the rib cage and lungs contract together with the diaphragm. When you breathe out, the rib cage and lungs relax. During quiet breathing, the intercostal muscles are the main driving force.

There are two types of muscles that drive inspiration. These are the accessory muscles of inspiration, which are found in the thorax and upper chest. Some of these muscles include the sternocleidomastoid, clavicular head, serratus anterior, and pectoralis major.

The muscles of the thorax also contribute to changes in thoracic cavity pressure. For example, when the diaphragm contracts, it lowers the alveolar pressure, which draws air in from the mouth. Similarly, when the diaphragm relaxes, the lungs release the air.

How To Assess and Influence Your Breathing

Abnormal breathing mechanics may be one of the key factors in the development of chronic myofascial trigger points throughout the body

Trigger point therapy can be a useful tool in releasing the musculoskeletal component of respiratory dysfunction and is especially useful when combined with other modalities, such as yoga, Feldenkrais, meditation, the Buteyko method and “breath therapy.”

Nothing in the body happens in isolation, and an exploration of breathing mechanics exemplifies this.

Breathing involves many sequences of coordinated muscular and visceral co-contractions.

Trigger points can often be palpated along the anterior inferior costochondral margin.

These trigger points should be contextualized with other relationships such as:

-

Submandibular inferior margin (often on the opposite side to the diaphragm trigger points)

-

Abdominal visceral fascia (greater and lesser omenta)

-

Spinal muscles (especially mid lumbar)

-

Abdominal muscles (especially transversus and rectus abdominus)

-

Pelvic floor muscles (pelvic diaphragm)

-

Thoracic spine and rib mobility

-

Intercostal muscles

-

Serratus musculature

-

1st rib mechanics

-

Scalenes, levator scapulae, and upper trapezius

Breathing patterns are often abnormal. Hyperventilation syndrome, panic attacks, and postural habit are increasingly diagnosed.

If untreated, these syndromes also have ongoing physiological consequences, such as respiratory alkalosis (too much carbon dioxide is exhaled by over-breathing).

Paradoxically, this situation is one of the key factors in the development of chronic myofascial trigger points throughout the body.

It may be interesting to note here that cranial osteopaths talk about eight diaphragms which all coordinate together in breathing: the diaphragma sellae, under the pituitary gland; the submandibular myofascial raphe, bilaterally; the thoracic inlet/outlet, bilaterally; the abdominal diaphragm; and the pelvic floor, bilaterally.

Abnormal breathing and trigger point formation

Garland (1994) suggested a sequence of musculoskeletal changes that may develop over time as a result of chronic upper chest respiration:

- Restriction in thoracic spine mobility (secondary to aberrant rib mechanics)

- Trigger point formation in scalenes group, upper trapezius, and levator scapulae

- Tight and stiff cervical spine

- Changes in tone of abdominal diaphragm and transversus abdominis (Hodges et al. 2001; McGill et al. 1995)

- Imbalance between weakened abdominal muscles and hypertonic erector spinae

- Pelvic floor weakness

This blog is intended to be used for information purposes only and is not intended to be used for medical diagnosis or treatment or to substitute for a medical diagnosis and/or treatment rendered or prescribed by a physician or competent healthcare professional. This information is designed as educational material, but should not be taken as a recommendation for treatment of any particular person or patient. Always consult your physician if you think you need treatment or if you feel unwell.

Learn More for Less

Unlimited access to all courses for just $19.95/mo